The book, which will be out in June, also dedicates a chapter to Sahib Kaur, who became the prime minister of Patiala at the age of 22, and went on to lead several battles, including one in which she beat back the Marathas at Ambala in 1794.

By Manraj Grewal Sharma : The Indian Express, May 28th 2022

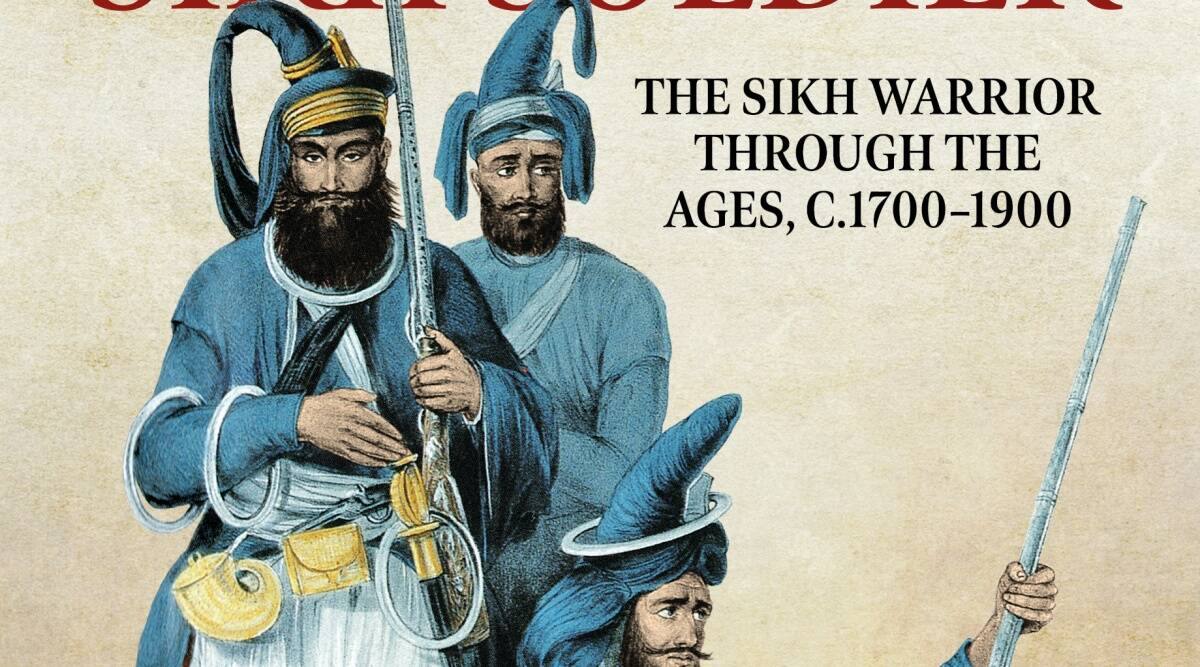

How the Sikh military tradition was formed and how it changed over 200 years. This is the subject of Gurinder Singh Mann’s forthcoming book – ‘The rise of the Sikh soldier: The Sikh warrior through the ages, 1700-1900’. Mann, a London-based historan and director of Sikh Museum Initiative in the United Kingdom, says the reason the book is special is because it doesn’t limit itself to male Sikh soldiers, but lavishes much attention to women warriors as well.

Two figures that Mann is particularly fond of are Rani Sada Kaur, head of the Kanhaiya misl, and Sahib Kaur, the prime minister of Patiala.

Sada Kaur, says Mann, was principally responsible for the rise of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. “Mother-in-law of the young Ranjit Singh, and mother to Mahtab Kaur, she was very pivotal to his early successes. She not only guided him in strategy and the art of brinksmanship but also provided him troops and arms when he took over Lahore and Amritsar.”

The book, which will be out in June, also dedicates a chapter to Sahib Kaur, who became the prime minister of Patiala at the age of 22, and went on to lead several battles, including one in which she beat back the Marathas at Ambala in 1794. “So compelling was her persona that she was able to get the support of all misl leaders. She even had people like Baghel Singh, founder of the Karorasinghia Misl, support her,” says Mann.

Sahib Kaur worked hard to keep the Patiala state intact. “Lot of people were trying to destroy it through politics but she managed to outmaneuver them. She also fought against an Irish adventuirer called George Thomas who held the territory of Hansi.”

Fascinated with his subject, Mann visited the royal cemetery of Patiala called ‘Samadhi-samadha’ but returned disapppointed. “The names of all the males were there. I was told that her samadh was there but I couldnot find the name Sahib Kaur who died young at the age of 30.”

The book describes key figures like Jassa Singh Ahluwalia (1718–83) better known as Sultan-ul-Qaum or (King of the Sikh Nation), who guided the Sikhs through the most turbulent times including the Vadhha Ghallughara (bigger holocaust), and Charat Singh Sukerchakia, the grandfather of Ranjit Singh, who showed his might against the Durranis in Vadhha Ghallughara (big holocaust). It also dwells on Hari Singh Nalwa and Akali Phula Singh without whom there would have been no Khalsa empire.

Then there is Lehna Singh Majithia, an inventor and technologist who was able to craft many guns and other innovations in warfare.

Mann says the book is unique insomuch as “it shows that the Sikh empire had diplomatic links with the British and the French as well as governments within South Asia besides recruiting European mercenaries.’’

The book is rich in images of relics and artefacts from various museums and private collections, some published for the first time.

It was while working on this book that Mann realised there was a yawning gap in history between Banda Bahadur who died in 1716 and Maharaja Ranjit Singh who ascended the throne in 1799. “Not enough is known about the Misl period that falls between 1700 and 1800.’’

Mann undertook a tour of Punjab and Haryana this summer to find out the misisng parts of the history puzzle. It was an uphill task as most traces of that turbulent history had been wiped off. But Mann also came across places and people with links to the Misls.

Some became mascots of the farm agitation that most people didn’t recognise. Mann says he was surprised when he saw farmers carrying sketches of Baghel Singh, head of the Karorasinghia Misl who had conquered Delhi in March 1783, as an emblem of victory.

The misl dominated the Ganga-Jamuna Doab between 1764 and 1800.

Mann visited many places like Thanesar, Ladwa, Chillondi (the base of Baghel Singh) in Haryana and drew a blank.

But he was in luck at Ahmedgarh, previously called Bahadurgarh, near Malerkotla where the locals knew about Baghel Singh. “They celebrate the conquest of Delhi called Dilli Fateh diwas in March every year.’’

Locals at Hariana village near Hoshiarpur, which is home to the samadh of Baghel Singh and his wife, also knew about the feisty general who outmanoeuvered the Mughals, Rohillas, Jats, Rajputs and the East India company, and commemorate his victory every year.

At Dhurkot, near Ludhiana too he came across people who told him about the history of Baghel Singh.

Then he found some physical evidence as well. At Yamunanagar in Haryana, there was a big fort of the Bhangi misl. And at Thanesar, he found descendants of Bhanga Singh.

At Ladhran in Ludhiana, he met with a family that traced its roots to the Nishanwali misl. A dilapidated fort tells the story of its chief Jai Singh Nishanvali. A few metres away is a gurdwara that still lights a jyot’’ (flame) in his memory.

The orginal article can be read here